This is the second in a series of five blogs that explore the 10,000 year history of human relationship to the land in the Piedmont region of North Carolina. Other blogs in this series include The Long Story of Catawba Run, European Colonization, Industrialization, and The Piedmont’s Next Chapter.

The First Humans

The forests of the Piedmont and nearby Blue Ridge Mountains provided a rich landscape to forage when the first human inhabitants walked into the North Carolina Piedmont about 10,000 years ago. Archeological evidence suggests that these Paleo-Indians most likely only visited the region, travelling from the coast to hunt deer, elk, bison, and bear in the forested foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

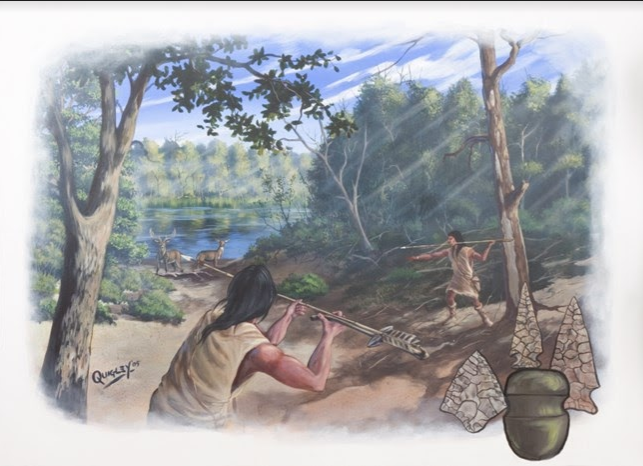

The Archaic Indians, direct descendants of the Paleo-Indians, slowly moved inland to establish seasonal camps and villages across the diversity of landscapes from the coast to the mountains of North Carolina. Archaic cultures are distinct from their ancestors by their use of finer bone and stone tools, new ways of weaving plant fibers into baskets, and the intentional cultivation of wild foods in their natural habitats. There is little evidence to suggest that Archaic peoples traveled far outside of their home region, but they did establish trade routes that brought them into contact with Native American tribes from other regions. Much of what we know about the Archaic Indians is based on archeological sites that have been found throughout the state, on high mountain ridges, along river banks, and across the rolling hills of the Piedmont.

Artist’s Conception of Archaic Indians of the Southeast Credit: Dean Quigley, National Park Service

The Woodland Culture

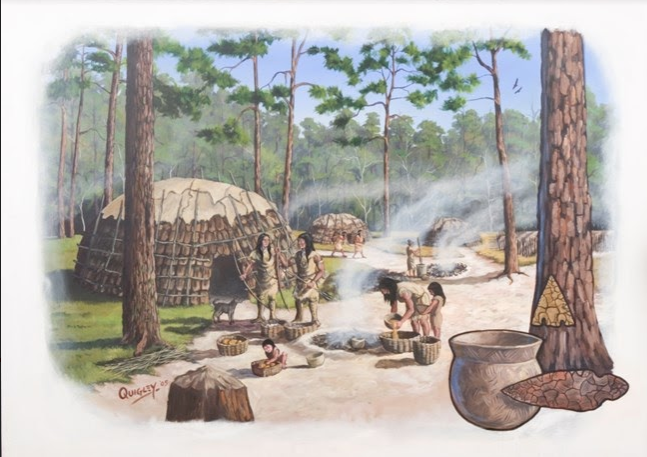

The evolution of agriculture in the Piedmont about 3000 years ago marks a distinct change to a new way of life that archeologists refer to as the Woodland culture. This culture evolved throughout the forest ecosystems of the Americas. Like their ancestors, the Archaic Indians, Woodland peoples still depended primarily on wild foods gathered from the forest, but they also began clearing fields to plant and harvest annual crops like corn, beans, gourds, and tobacco to supplement their food supply. The bow and arrow, pottery, tobacco pipes, and beads and other ornaments made of shell and clay also came into common use during this period.

As Woodland family groups settled near productive agricultural or hunting grounds in the Piedmont region, permanent villages began to develop along the major stream valleys where soils were best suited to farming annual crops. Housing in these early villages typically consisted of lodges made of bark or thatch that were furnished with straw or cane mats, pottery, baskets, and wooden utensils. Most villages included a council house for public gatherings and some were surrounded by protective palisades.

Artist’s Conception of Woodland Indians in the Southeast Credit: Dean Quigley, National Park Service

Artist’s Conception of a Woodland Indian Village Credit: UNC Research Laboratories of Archaeology

Like many indigenous cultures worldwide, Woodland tribal society was generally organized by leaders rather than rulers, governed by consensus rather than decree, and directed by a sense of community more than by individualism. Community rituals marked the passage of time and seasons and supported the expression of a rich spiritual life that recognized and honored a reciprocal relationship between humankind and nature.

The Mississippian Culture

About 1000 years ago, Mississippian peoples began moving into Carolina Piedmont as they expanded their settlement and trade networks beyond the Mississippi River Valley. Although descendants of Woodland cultures based in the Midwest, the Mississippian people abandoned the ways of their ancestors in favor of a new life based on the intensive production of corn as a staple food. This shift to a reliance on intensive agriculture was accompanied by a change in social relations as populations increased, a complex class system and specialized occupations developed, and political and religious power became concentrated in major metropolitan areas ruled by chiefdoms.

The Mississippian peoples developed widespread trade networks extending from the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. Map Credit: H. Roe

Mississippian settlements were dominated by a large pyramid-shaped central mound, topped by temples and meeting houses, set in the center of a grand public space. Individual homes surrounded these public grounds and extensive cultivated fields stretched beyond the homes. The Mississippian people established many settlements throughout the Southeast region, including several in the Piedmont region of the Carolinas. The largest settlement was Joara, a regional political center established on a 12-acre site on the west bank of Upper Creek near present-day Morganton and about 10 miles northeast of Catawba Run.

Artist’s Conception of a Late Mississippian Village. Credit: H. Roe

By 1500, the Mississippian trade network was under severe social stress and near collapse as a result of damaging deforestation, soil degradation, and over-hunting in areas of concentrated population. Other contributing factors included greatly reduced corn yields caused by decades of long term drought and an increase in the frequency and intensity of damaging flooding in the Midwest. Mississippian settlements in the Southeast were abandoned and indigenous peoples the Carolinas largely returned to Woodland ways of life.

Just before the arrival of the first European colonists in 1550, it has been estimated that more than 100,000 Native Americans were living in present-day North Carolina. The Catawba were one of largest tribes in North Carolina at this time, with a population estimated to be between 15,000 and 25,000 people.

The People of the River

The Catawba people inhabited a large area in the Carolina Piedmont and Southern Virginia. Calling themselves, yeh is-WAH h’reh or “people of the river,” their lives were based along the banks of the Catawba River watershed. They lived in villages surrounded by palisades or walls and in homes with rounded tops made of bark. They had a large council house and sweat lodge in each village, as well as an open plaza for meetings, games and dances.

Descendants of Woodland peoples, the Catawba were farmers, hunters, and fishers who planted crops in the rich bottoms lands along the river. They were a powerful tribe and were well-respected by other tribes in the region as fierce warriors.

Trade was common between the Catawba and the colonists and over time, the Catawba became allied to the Europeans and their way of life. The Catawbas emerged as a major broker for trade between Virginia and the Carolinas – trading deer skins for muskets, knives kettles, and cloth. Their pottery, made from the clay of the river banks of their land, was a highly valued trade item.

Although the Catawba had good relations with the colonists, their population was decimated by diseases introduced by the colonists – particularly a series of smallpox epidemics in the 1600s. By the mid 1700s the Catawba population dropped to just 1,000 people.

After the Revolutionary War, colonists began leasing land from the Catawba to farm, but ultimately desired to take the land as their own and pressured their state governments to do so forcibly. With their population greatly depleted and under relentless pressure from European colonists for their land, the Catawba Nation was further weakened by the loss of some of its people, who left to join other, larger tribes to the west. Believing that the Catawba would soon be wiped out anyway, the South Carolina government negotiated an agreement with the Catawba Nation: in exchange for one acre of land near Rockhill, South Carolina, the Catawba would relinquish title to 144,000 acres of their homeland.

Despite the ravages of war, colonization, disease, and displacement during the colonial period, the Catawba people persisted. Their long fight for federal recognition was won in 1990 and they remain the only recognized Native American tribe in South Carolina. Today, you can find the Catawba living on ancestral lands that they have inhabited for over 6,000 years. As of 2010, the Catawba Nation has 841 members.

The Catawba Nation is self-governed and provides a multitude of services to its members related to cultural preservation and affairs, housing, job placement and scholarships. The Catawba people are still renowned for their traditional pottery, with current day tribal members cultivating their 4,000 year-old cultural legacy. The Nation has multiple businesses and planning initiatives including projects related to organic farming, sustainable energy initiatives, hospitality, and recreation.

Modern Catawba people celebrating their ancestry at the annual Catawba Pow Wow. Usually held in the Spring, the Catawba Pow Wow allows Catawbas and other Indigenous people and tribes to celebrate and honor ancestry together with singing, drumming, dancing, vendors, and more. Credit: Catawba Nation

Catawba Run is 275 acres of old growth, unmanaged regrowth, and sustainable pine plantation located in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, near Nebo, just west of Morganton. This land is the setting for Foragable Community’s next demonstration of our shared values: to use ecological management practices and resilience principles to restore the health and wellbeing of degraded landscape, and concurrently have a positive impact on the lives of people who participate in this vision of redemption and renewal.

The Catawba Indian Nation are the descendants of the original inhabitants of land that we call Catawba Run. The Catawba, or “the people of the river” pronounced yeh is-WAH h’reh in their native tongue, were farmers, renowned potters, and stewards of the land in most of the Piedmont of South Carolina, North Carolina, and Southern Virginia. Foragable Community acknowledges that Catawba Run is on this ancestral land.

Sources

From the Encyclopedia of North Carolina

American Indians Parts 1 – 6. American Indians have populated the region that includes modern-day North Carolina continuously for more than 10,000 years and was home to many flourishing communities of indigenous peoples before the arrival of European explorers in the mid-1500’s. Since European contact, the history of American Indians in North Carolina, as elsewhere in the United States, often has been marked by conflict and struggle. North Carolina’s official policy of removal of American Indian people to reservations in Oklahoma and elsewhere struck a terrible blow to the state’s indigenous population. Nevertheless, communities of American Indians have persisted and evolved in the face of complex and often conflicting relationships with their non-native neighbors. Today, the state is home to two of the largest Indian tribes east of the Mississippi River, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and the Lumbee Indians. Native Americans in North Carolina have established themselves as vital participants in the state’s social, cultural, economic, and political spheres.

Native American Settlement of NC. Over four hundred years ago, English colonists encountered many Native Americans along the coast. At that time more than thirty Native American tribes were living in present-day North Carolina. They spoke languages derived from three language groups, the Siouan, Iroquoian, and Algonquian.

The Catawba Indian Nation is the only federally recognized tribe in the state of South Carolina. “We show that we are proud of our past by embracing our culture and sharing it with others. We presently have a wide variety of programs and services available to enhance the lives of our citizens. And we are preparing for the future of the tribe through education, economic development, and planning.”

Other Related Resources

Preserving the Past: A Guide for North Carolina Landowners. As a landowner, you probably know of your responsibility to protect and preserve soil productivity, water quality, biological diversity, and wildlife habitat. But you may not be aware of other valuable resources potentially on your property: archeological artifacts, historic structures and landscapes, and culturally important vegetation. These are known collectively as cultural resources, and this publication will help you learn more about identifying, protecting, and conserving these resources on your land through the creation of a preservation plan.