This is the third in a series of five blogs that explore the 10,000 year history of human relationship to the land in the Piedmont region of North Carolina. Other blogs in this series include The Long Story of Catawba Run, Indigenous Cultures of the Piedmont, Industrialization, and The Piedmont’s Next Chapter.

European Colonization

In the early 1500’s, the first Spanish and English explorers travelling through present-day North Carolina encountered numerous Native American communities of the Woodland culture. As the first European colonists began to arrive in mid-century, an estimated one hundred thousand Indigenous people inhabited the region. They mostly lived in small villages, grew crops of maize, tobacco, beans, and squash. They tended, gathered, and hunted wild foods and traded with other tribes in the region and beyond. Two hundred and fifty years later, the Native American population of the region had declined to just twenty thousand as a result of European colonization.

First Contact

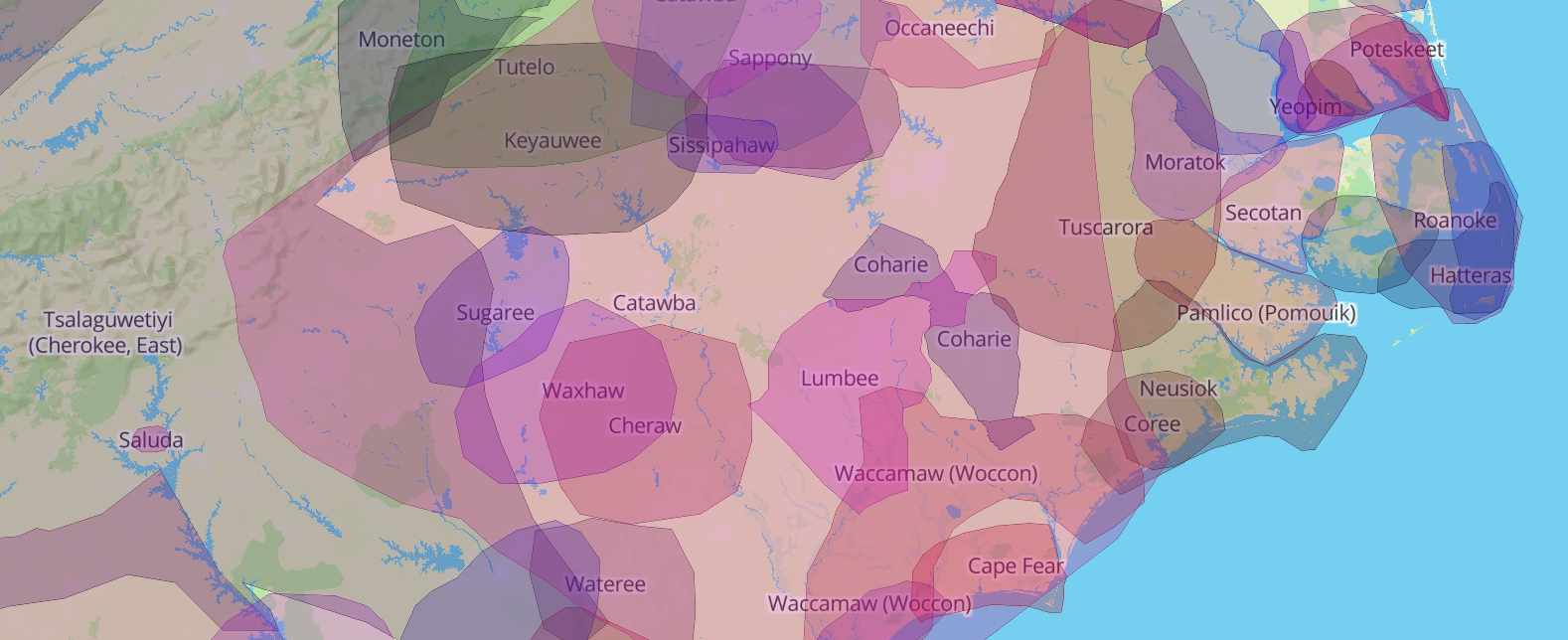

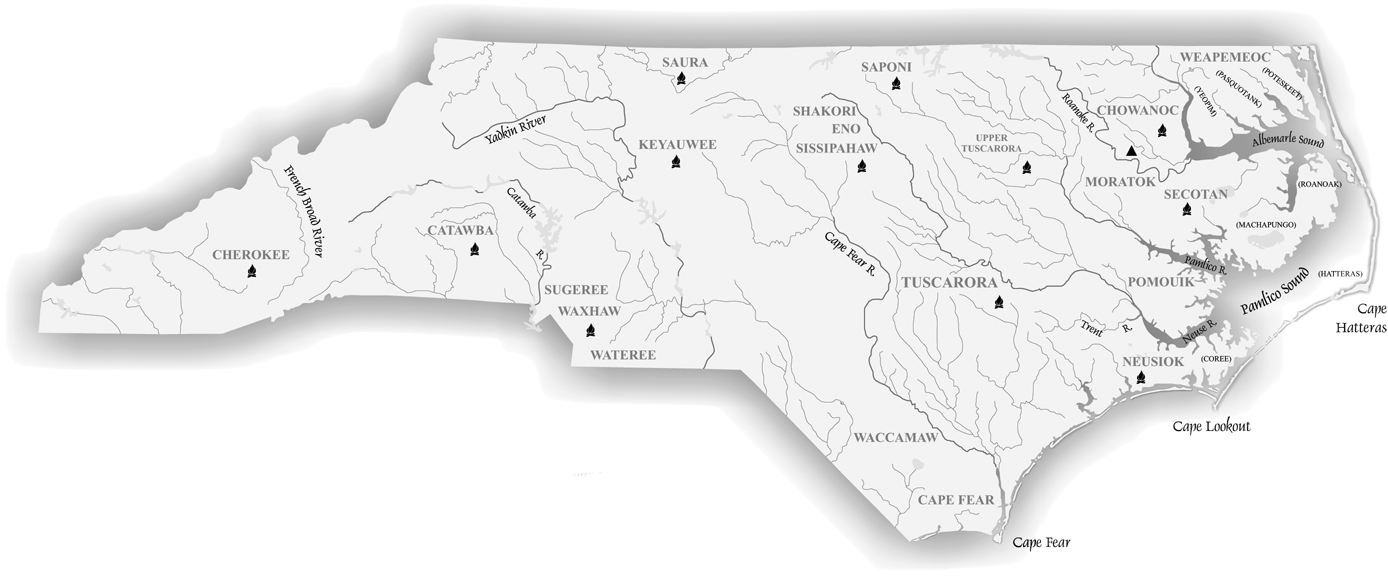

At the time of first European contact, Native Americans from Iroquoian, Siouan, and Algonquian linguistic groups inhabited the landscape of present day North Carolina from the outer banks to the Appalachian Mountains. Two Iroquoian tribes, the Cherokee and the Tuscarora, thrived in the Appalachians and the Coastal Plains. Algonquian tribes held lands in the northeast included the Hatteras, Moratok, Croatan, Secotan, Pamlico, Roanoke, and Weapemeoc (Yeopim).

Siouan tribes flourished throughout the central Piedmont, the Pee Dee River Valley, and the Lower Cape Fear region. These tribes included the Cape Fear, Catawba, Keyauwee, Occaneechi, Pee Dee (or Pedee), Sappony, Sissipahaw, Saura (Cheraw), Tutelo, Waxhaw, and Waccamaw peoples.

This image was created with an interactive map of the world created by Native Land Digital to honor of all the Indigenous Nations of lands colonized by Europeans. It seeks to invite all people — Native and non-Native alike — to remember that these colonized lands were once inhabited by autonomous Native peoples. These Native peoples called the land by many different names according to their own languages and geographies. You can go to Native Land Digital and input your address on the map to learn more about the Indigenous people who inhabited your home before European colonization.

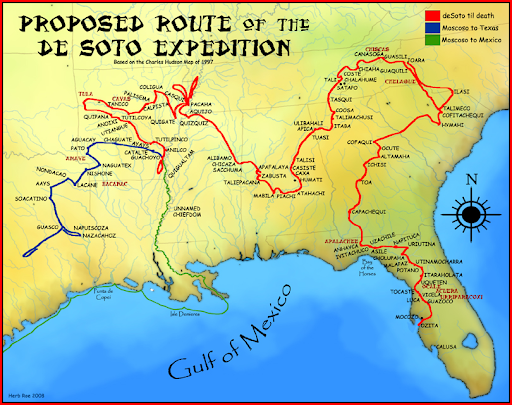

In the early years of the 1500’s, Spanish expeditions pushed along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts and into the interior of what is now the southeastern United States. The Spanish hoped to find new trading routes to the Pacific Ocean and to Mexico’s gold mines. They were also tasked to document the natural resources in the lands that they passed through.

The first recorded contact between Europeans and Native Americans in the present day Carolina Piedmont was made during a Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto. The expedition set out in 1540 and over four years travelled deep into the interior of the Southeast and Mid-South. Twenty years later Juan Pardo led another Spanish expedition that followed in de Soto’s footsteps.

The goal of the Pardo expedition was to explore lands to the north and west of Spanish Florida, to claim these lands for Spain while pacifying local inhabitants, and to find an overland route from the east coast to the silver mines in northern Mexico. In January 1567, after travelling through the Carolina Piedmont along the Wateree and Catawba rivers, Pardo and his men arrived at Joara, a large native town in the upper Catawba Valley near the eastern edge of the Appalachian Mountains.

A map showing the proposed route of the de Soto Expedition, based on the 1997 Charles Hudson map. Image Credit: Herb Roe CC BY-SA 3.0

At that time, Joara was the largest and the most powerful of the Native towns in the western Piedmont region of North Carolina. The town occupied about 10 acres of bottomland dominated by a central mound on the west bank of Upper Creek located about 8 miles north of modern day Morganton. Archeological evidence suggests that Joara served as the political and ritual center of a Mississippian-style chiefdom that ruled at least 26 neighboring villages located in the upper Catawba River watershed. Joara’s location also allowed the chiefdom to control several important trading paths through the Piedmont region.

Before leaving Joara, Pardo’s forces built a fort nearby and left 30 soldiers to maintain it. Eighteen months later, amid increasing conflict with the Spanish, Joara warriors killed the soldiers and burned down the fort. It would be nearly 200 years before Europeans would make another attempt to colonize the upper Catawba watershed.

North Carolina’s First Colonists

The first European colonists to successfully settle in modern day North Carolina immigrated overland from their home colonies in Virginia and South Carolina to the coastal plain region of North Carolina in the mid-1600’s. During this early period of colonization, poor harborage and a treacherous coastline limited arrivals by sea.

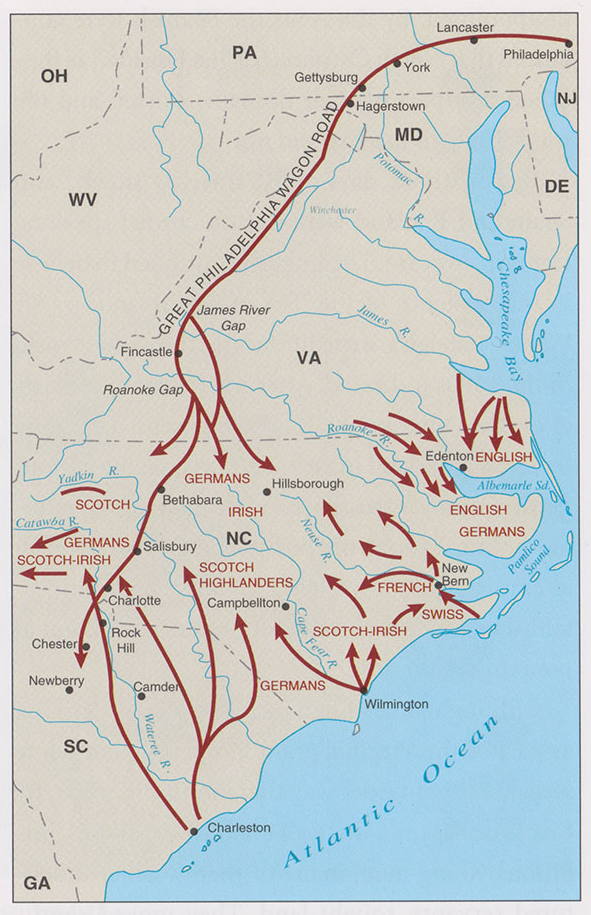

By the early 1700’s, groups of French Huguenot, German Palatine, Swiss and Scottish colonists came directly from Europe to settle along the great river valleys of the North Carolina coastal plain. Scottish, Irish and German colonists began to flow into the Piedmont region by mid-century, many travelling overland through the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia to settle in the central and western portions of the Piedmont region.

Flow of Colonists Into North Carolina in the 1700’s

Credit NCPedia

Many of North Carolina’s Native Peoples tried to live and work cooperatively with these newcomers for a time. They taught the colonists Indigenous agricultural techniques for the cultivation of corn, tobacco, and other traditional Native crops as well as fishing and other necessary survival skills. In return, the European settlers offered Native Peoples crops, livestock and manufactured goods from their homeland. This trade began to change the way Native Peoples related to each other and how they came to view the settlers.

The use of manufactured goods such as metal tools, guns and ammunition, increased the vulnerability of Native Americans to manipulation by European traders and colonial authorities, who often turned one Native tribe against another for political, economic, or other purposes. Competition for the growing colonial trade in Native goods, such as deerskins and enslaved Native Americans, also caused competition among Native tribes that often ended in violence and death.

These changes grew more damaging as European settlement expanded and led to a massive decline in Native populations during the colonial period. The century between the arrival of the first English colonists to the eve of the Revolutionary war was one of deadly and unrelenting conflict: between colonial powers and allied tribes, between Native Americans and colonists staking claim to the same land, and between Native American tribes seeking relief from the increasing pressures of colonization.

Recurring waves of European disease epidemics also played a major role in the destruction of North Carolina’s Indigenous cultures. Massive smallpox epidemics in 1695 among the Pamlico Indians on the coast, and a 1738 outbreak in the mountains that reduced the Cherokee population by half, are just two examples of devastating impact of epidemic disease on Native populations during the colonial period.

The European colonization of the Carolina region signaled an era of tragic change for its Indigenous peoples, one marked by the taking of their lands, the loss of their traditional ways of living and the unrelenting decline in their population.

Native American Tribes in the North Carolina Colony in 1711 Image Credit: Map by Mark Anderson Moore, courtesy North Carolina Office of Archives and History

Colonization of the North Carolina Piedmont

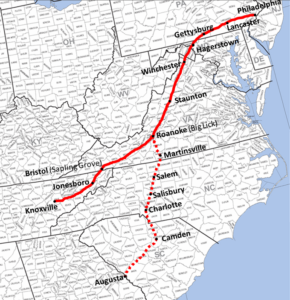

The Great Wagon Road

North Carolina colonists from Europe or of European descent remained in coastal regions of the state until about forty years before the American Revolution (1775– 1783). The rapids and waterfalls that mark the transition between the coastal plain and Piedmont made traveling on rivers difficult and discouraged migration west from the coasts. The Piedmont backcountry offered colonists new challenges and opportunities. The region’s limestone and clay soils supported forests and grasslands on rolling hills stretching west to the high blue ridges of the Southern Appalachians. The Piedmont’s swift-flowing, shallow streams and narrow rivers were not good for boat traffic, but offered excellent sites for mills and farms.

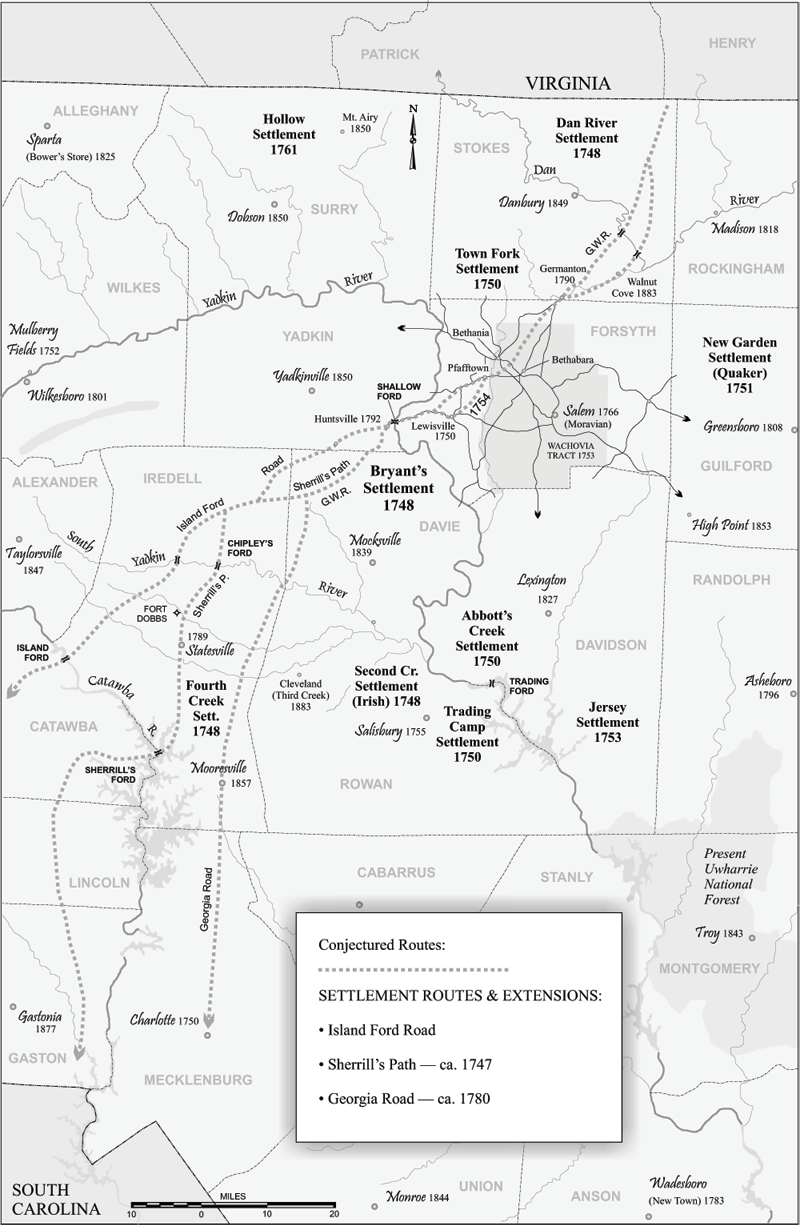

Though few roads ventured into the backcountry, two were vital to settlement of the region. The Great Indian Trading Path began in Petersburg, Virginia, and traveled southwest through the Piedmont to present-day Mecklenburg County. Used for centuries by Native Americans, in the mid-1700s settlers began using it to travel into North Carolina from northeast part of the Virginia colony. The Great Wagon Road, which stretched from Pennsylvania to North Carolina via the Shenandoah Valley of Virgina, was the second major road bringing colonists to the Piedmont.

During a period of calm following years of violent conflict in the region, the colonization of the Piedmont began to accelerate in the mid-1700’s. Colonists arrived in such great numbers to the Piedmont that the North Carolina colony’s population more than doubled between 1765 and 1775. Many early Piedmont colonists were descendants of the Scotch- Irish and German peoples who had immigrated from Europe to the Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia colonies. As land become scarce and expensive in their home colonies, descendants of the first colonists and recent arrivals from Europe travelled south on Great Wagon road to find less expensive lands on which to settle. The Great Wagon Road took these colonists south into the western Piedmont of North Carolina to the ancestral lands of the Catawba people.

Map of the Great Wagon Road and Offshoots in North Carolina. Image Credit: Joe A. Mobley, the University of North Carolina Press, and the North Carolina Office of Archives and History

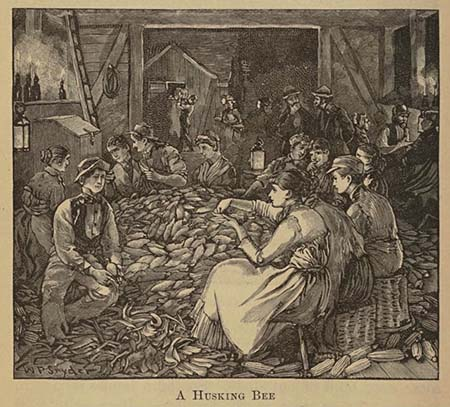

These immigrants brought new economic and settlement patterns in the region. They clear-cut forested uplands to build homesteads and grow crops and they grazed livestock in the open forests and grasslands that had been created and maintained by the Catawba for generations. They grew corn for their own use, wheat and tobacco for export, raised cattle and hogs and drove them in large numbers to northern and southern markets.

Family and friends gather together to husk corn on a colonial farm. Image Credit: NCPedia

Trade of the time flowed along three principle routes – to the north on the Great Wagon Road through Virginia – to the east on new overland roads, and to the south on the rivers that flowed into South Carolina. Typical products produced for trade in the Piedmont region in the late 1700’s include: beef, pork, wheat flour, Indian corn, tobacco, livestock, raw hides, deerskins, tobacco, flaxseed, butter, tallow, and naval stores. In less than 50 years, all the best land in the North Carolina Piedmont had been occupied, forcing colonists arriving after 1780 to head west into the mountains of North Carolina and beyond.

As the population of the Piedmont increased, small villages began to develop – typically consisting of little more than a log courthouse/jail that served as a county seat, a tavern, a few stores, and a small cluster of houses. Tradespeople of many kinds settled in the region – blacksmiths, brewers, weavers, carpenters, coopers, potters, rope makers, wagon makers, and wheelwrights – and contributed to the development of a local industry that produced needed goods.

Many of these growing villages had stores, taverns, craft shops, churches, and eventually schools where people could trade for or buy supplies they could not produce locally, socialize with friends, get a basic education and gather together to practice spiritual traditions. The landowners and townspeople in this rapidly growing area of the North Carolina colony relied on the forced labor of indentured servants and enslaved people from North America and West Africa.

Enslaved Peoples in the Colonial Piedmont

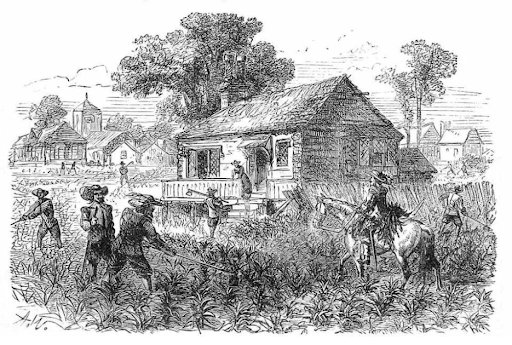

The Brutality of Slavery in the Carolina Colony.

Agricultural patterns, especially the production of labor-intensive cash crops such as tobacco, rice, cotton and indigo determined the patterns of labor in the Carolina colony. From the coasts to the western mountains, European colonists and their descendents relied on the labor and skill of enslaved Africans and Native Americans for a great variety of economic activities including hunting and fishing, crop and livestock production, carpentry, general construction, mining and manufacturing.

The first enslaved Africans to work in the Carolina colony were taken from Guinea, West Africa in the mid-1600’s; however most landowners in the Carolinas purchased enslaved African laborers from South Carolina, Georgia, and the Chesapeake region. The enslaved African population of the colony grew from 800 in 1712 to 41,000 in 1767. About 90 percent of the enslaved agricultural field work. The remaining 10 percent were mainly domestic workers and a small number worked as artisans in skilled trades.

Early in the colonial period, it was common for enslaved Native Americans to work alongside enslaved Africans and European indentured servants as agricultural laborers, domestic servants, and in skilled trades. With labor at a premium in the colonial economy, there was no shortage of people seeking to purchase slaves and many colonists supplied the Native American slave trade to accumulate capital. In South Carolina, and to a lesser extent in North Carolina, Virginia, and Louisiana, Native slavery was a central means by which early colonists funded economic expansion.

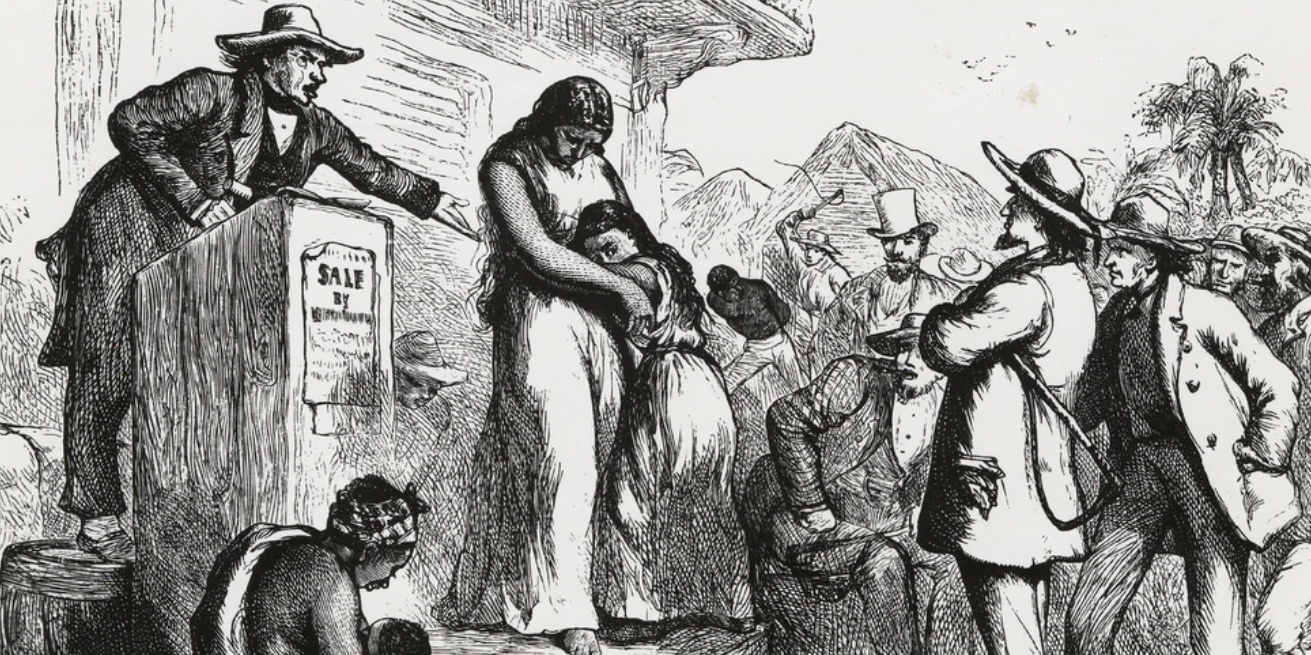

Native Americans sold into slavery were kidnapped, captured by raiding parties, or defeated in battle. Although most Native Americans enslaved in the Carolina colony were sold north to the New England colonies or south to the West Indies, almost 2000 were working in the colony in 1715. From 1670 to 1720, more enslaved Native Americans were shipped out of Charleston, South Carolina, than enslaved West Africans were shipped in.

Native American woman and child on the auction block. Image Credit: The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

On the Eve of Revolution

On the eve of the Revolution, North Carolina was home to a remarkable diversity of people. The northern coastal region had been settled by the English for more than a century. There and along the lower reaches of the Cape Fear River wealthy planters used enslaved Africans to create the basis for a plantation society. In the western mountains, the Cherokee remained committed to the fight for their land and traditional ways of life despite continuous land cessation to the English and French – amounting to over 50,000 square miles in total – and the loss of half of their population to disease. In between the mountains and the coast, English, Scotch-Irish, German, and Highland Scottish colonists made new homes in the dense forests of the Piedmont.

A century of colonization transformed the lives of North Carolina’s Indigenous peoples. Weakened by disease, continuous warfare, enslavement and the relentless theft of their land by colonists and colonial governments, the remnants of the 20 independent tribes with ancestral lands in the Piedmont left the colony or headed south to join the Catawba near present-day Charlotte. North Carolina east of the mountains had been cleared of its Indigenous peoples and opened for European settlement.

Of the three most powerful tribes in present day North Carolina at first contact, only the Cherokee people remained in North Carolina with their culture and ancestral lands intact. The Tuscarora withdrew to New York, where they became the sixth nation of the Iroquois Confederacy. The remnants of the Congaree, Sugaree, Wateree, Waxhaw, and Shakori joined the Catawba on the North Carolina-South Carolina border south of present-day Charlotte to form the Catawba Nation.

The inhabitants of the largest towns in the colony differed markedly from their rural neighbors in their work, social position, and personal opportunity. The people of North Carolina were spread through the Piedmont and Coastal Plain in isolated enclaves that differed markedly in politics, language, religion, and every other social and cultural characteristic, so much so that few saw themselves as members of the same society.

Although these newcomers might agree on little else, they did share an admiration for the great forests of their new home. Despite more than a hundred years of European colonization, in 1770 the great North Carolina wilderness still felt very close. Although there were new towns growing in clearings on the banks of the great rivers, new open fields planted with crops and livestock grazing in pastures, and new homes ranging from simple homesteads to great plantations – all were built against the backdrop of seemingly endless forest.

—————————

Resources

From NCPEDIA

American Indians Part iii: Indian Tribes from European Contact to the Era of Removal

The Fate of North Carolina’s Native Peoples

The Growth of Slavery in North Carolina

Other Resources

The Way We Lived In North Carolina: An Independent People

American Indian Slavery in Carolina

Indian Slavery in the Americas

———–

Catawba Run is 275 acres of old growth, unmanaged regrowth, and sustainable pine plantation located in the Piedmont region of North Carolina, near Nebo, just west of Morganton. This land is the setting for Foragable Community’s next demonstration of our shared values: to use ecological management practices and resilience principles to restore the health and wellbeing of degraded landscape, and concurrently have a positive impact on the lives of people who participate in this vision of redemption and renewal.

The Catawba Indian Nation are the descendants of the original inhabitants of land that we call Catawba Run. The Catawba, or “the people of the river” pronounced yeh is-WAH h’reh in their native tongue, were farmers, renowned potters, and stewards of the land in most of the Piedmont of South Carolina, North Carolina, and Southern Virginia. Foragable Community acknowledges that Catawba Run is on this ancestral land.